AI Acquihire Deals Benefit a Few at the Cost of Many

There Must Be a Better Way, Especially for Abandoned Employees

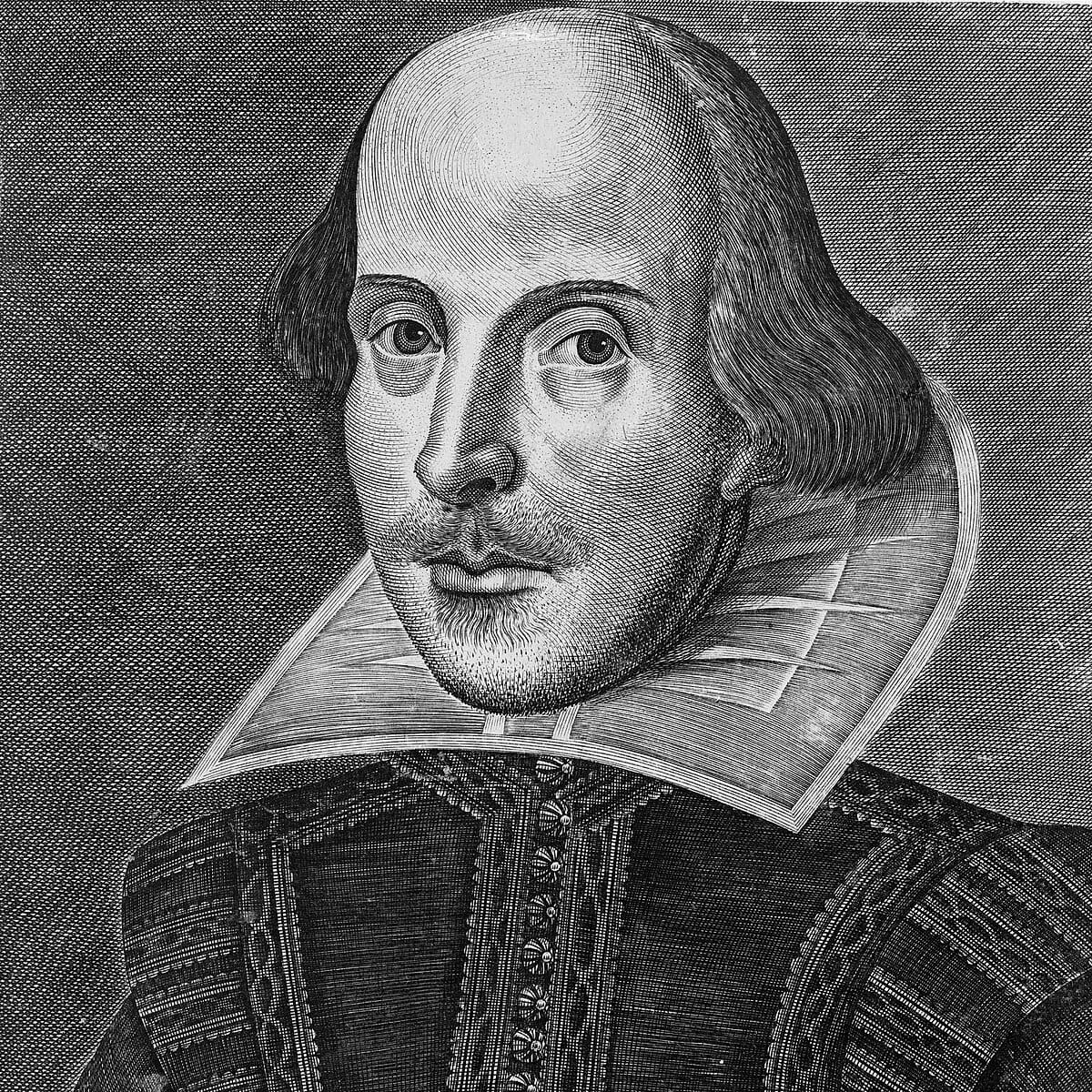

Shakespeare wasn’t keen on lawyers. He understood that what is strictly legal isn’t always, or necessarily, ethical. If Shakespeare were around today, he’d perhaps be motivated to digitally pen a satire on the legal punctilios and moral failings of Big Tech’s latest craze: the acquihire.

Lawyers are essential to the inception and execution of the acquihire, helping their cash-rich technology clients circumvent the screening and review processes associated with conventional acquisitions, which are subject to antitrust regulations and reviews.

Acquihires of AI startups are blooming like tulips in Amsterdam in April. All the usual Big Tech suspects are pursuing acquihire deals, which involve the procurement of founders, leading researchers and scientists, and other select principals at target companies. Left behind, like dry husks, are zombie companies, filled with the unfortunate employees who didn’t receive golden tickets to the acquiring company. Abandoned, they must fend for themselves, without the leadership or star innovators who drew them to the company and attracted the investment capital that sustained development.

Let’s consider who benefits from such deals. First, the buyer benefits from the AI acquihire. The purchaser gets valuable talent, often leaders in a specific realm of AI. Not only do the buyer get the prodigious talent, but it also obtains it without having to run the gauntlet of an antitrust review process, which can be lengthy and can even result in rejection of the deal.

Who else benefits? Well, those subject to the acquihire (the acquihirees?) — the founders of AI startups and their hand-picked superstars — get a rich payoff, and the additional benefit of the largesse and resources that only a Big Tech behemoth can provide. Conversely, of course, they’re now under the bureaucratic fetters of an industry giant, but they might be able to negotiate certain personal exemptions from the rules that apply to standard-issue employees. Anyway, the money and privilege they receive as part of the deal can ameliorate any pain incurred from bureaucratic assaults on the soul. To paraphrase a once-famous television commercial, certain types of memberships have their privileges.

It’s a Small Club, and You’re Probably Not In It

Investors in the plundered startup also benefit. Sure, the startup companies subject to acquihires are left rudderless and adrift, but if the VCs and seed investors are compensated by the buyer, which pays off the investors to avoid bad blood and well-heeled resistance.

Oh, and lawyers obviously benefit. Not only did they conceive these mutant transactions, but they perform essential roles in bringing them to fruition.

Let’s now consider who doesn’t benefit. That’s easy: the employees who are left behind, in the hollowed-out husks of zombie companies. These are people who get the business — and not in a good way. They find themselves abandoned by people they trusted, by the people who sold them a compelling vision and a promise of future prosperity that ultimately vanished in a puff of acquihire smoke.

Employees who gravitate to startups often take less in immediate compensation for the deferred gratification of potentially larger recompense at a later date, namely the realization of a lucrative exit.

I know. There are no certainties in life. Employees at startups understand that the company could flounder and sink without a trace. Companies fail all the time. We know that, and when we accept a job at a startup, we understand that we might never reach the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

The fate of those marooned in a zombie company, however, is of a different order. The company didn’t fail, at least not in the conventional sense. That’s why those on the wrong end of an acquihire feel they’ve swallowed such a bitter tonic.

Ghost Ships and Ghouls

In an acquihire, the chosen few (quite literally) escape from the ghost ship to collect their bounty on the corporate raider’s opulent vessel. The crew members left behind on the good-ship startup helplessly watch as the people who hired them casually wave an indifferent farewell. That tableau doesn’t exactly exemplify the comradely ethos of “all for one and one for all,” does it?

Before the acquihire raised its ugly head, a company failure was shared, more or less, by everybody in the company, from those at the top of the corporate hierarchy to the most recent hire.

At this point in our discourse, you could put on your Social Darwinian shades, and say you don’t see the problem: Life is hard, there are no guarantees, and only the fittest survive. You could do that, but I think you’d be missing the point. Companies survive on trust. Why would anybody join a startup, deferring maximization of their near-term wealth, if they had the foreknowledge that the founders would leave them stranded at the first come-hither proposition of a Big Tech monolith?

In addition to the employees, also receiving a kick to the shins are the competitive dynamics associated with a thriving market. Consequently, consumers and businesses that procure and use AI services will have fewer options at their disposal. Worse, the options at their disposal will be controlled by unprecedentedly large corporations, whose oligopoly status will encourage the usual abuses and benign (and not-so-benign) neglect that often accompany captive markets. If startups are quashed and eviscerated before they reach adolescence, what alternatives will customers — enterprises and consumers — have to Big Tech purveyors?

These are problems that require remediation, for startup employees and for the common good. We can all hope that government bodies close the legal loopholes that allow acquihires. We can hope that government compels Big Tech to continue to jump through the mandated regulatory hoops and over the requisite obstacles associated with conventional M&A transactions.

You might have noticed that I used the aspirational word hope. As we know, hope is not a strategy. There’s a possibility, perhaps a probability, that the current U.S. government, and perhaps other governments worldwide, will assume an aggressively deregulatory, laissez-faire attitude, allowing Big Tech to embrace the philosophical prescription of crackpot occultist Aleister Crowley, who once declared that “do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law."

That sort of impractical guidance results in complete dysfunction, with side orders of pervasive buyers’ remorse and systemic conflict.

Well, what can we do that is more practical than the optimistic yearning for a better tomorrow? Beyond hope, there is recourse to informed activism by startup employees.

Suggestions for Your Consideration

I have some ideas for the consideration of stiffed employees. First, no longer trust the eloquent founders when they ask you to put blind faith in their altruistic leadership.

As an employee, you’re allocating your labor, which has a market value, to a startup company. That company has asked you to take a reduced level of current compensation in exchange for a long-term payoff, if it comes to fruition, that will exceed what you could have earned elsewhere over the same duration.

Even if you find the founder’s narrative compelling, you should insist on contractual stipulations that ensure fair compensation in the event of an acquihire, irrespective of whether you join the acquiring company or get left behind. Unfortunately, such a negotiating stance will only succeed if a large proportion of prospective startup employees take a line similar to yours. Then again, if the founder is unwilling to accept such reasonable terms, you know you’re just a cog in the machine, as dispensable as the office furniture.

Here’s another idea that depends on collaboration, though the bosses might call it conspiratorial collusion. Perhaps it’s time for some form of unionization in the technology industry. It’s probably not possible — unions are seen today as quaint relics of the 20th century — but desperate times require creative thinking. Perhaps old can be new again, new wine in an old bottle.

In the imposing shadow of AI, founders and investors have all the power. Employees, who thought they had power about a decade ago, are dismayed to learn that they have a lot less leverage now. If their interests are to be respected, tech employees will have to regain leverage, and I think they can only derive such power through some form of collective action. (Yes, what I’m suggesting is anathema to the pseudo-libertarianism of our tech overlords, but I’ll wear the iconoclast mantle, provided it’s the right color scheme, with pride.)

As some philosophers and political scientists contend, we might be heading into an era of oppressive digital feudalism. Under the aegis of the original form of feudalism, one couldn’t count on the noblesse oblige of the ruling class. I don’t think you can count on a voluntary generosity of spirt from today’s lords of the AI manor, either. As startup founders, investors, and megabucks acquirers share their bounty and make common cause, digital knowledge workers will have to figure out how they can effectively defend their interests.

Then again, if an AI bubble bursts, or current AI growth is otherwise decimated, this discussion might become moot, at least temporarily. We’ll explore that question next.